The key points:

- Immigration has significantly shaped Australia's population growth for decades. This has boosted GDP and the labour force, without negatively affecting labour market outcomes because it adds to both the demand and supply for labour.

- Immigrants in Australia tend to be younger and more educated than the native population, which leads to better productivity and wages over the long term. However, they are also more concentrated in major cities where competition for housing and infrastructure is already intense.

- In the long run, Australia will benefit from adjusting the composition of the migrant population by implementing policies that address genuine skill shortages, reduce concentration in capital cities and lower the pressures of an ageing population.

Introduction

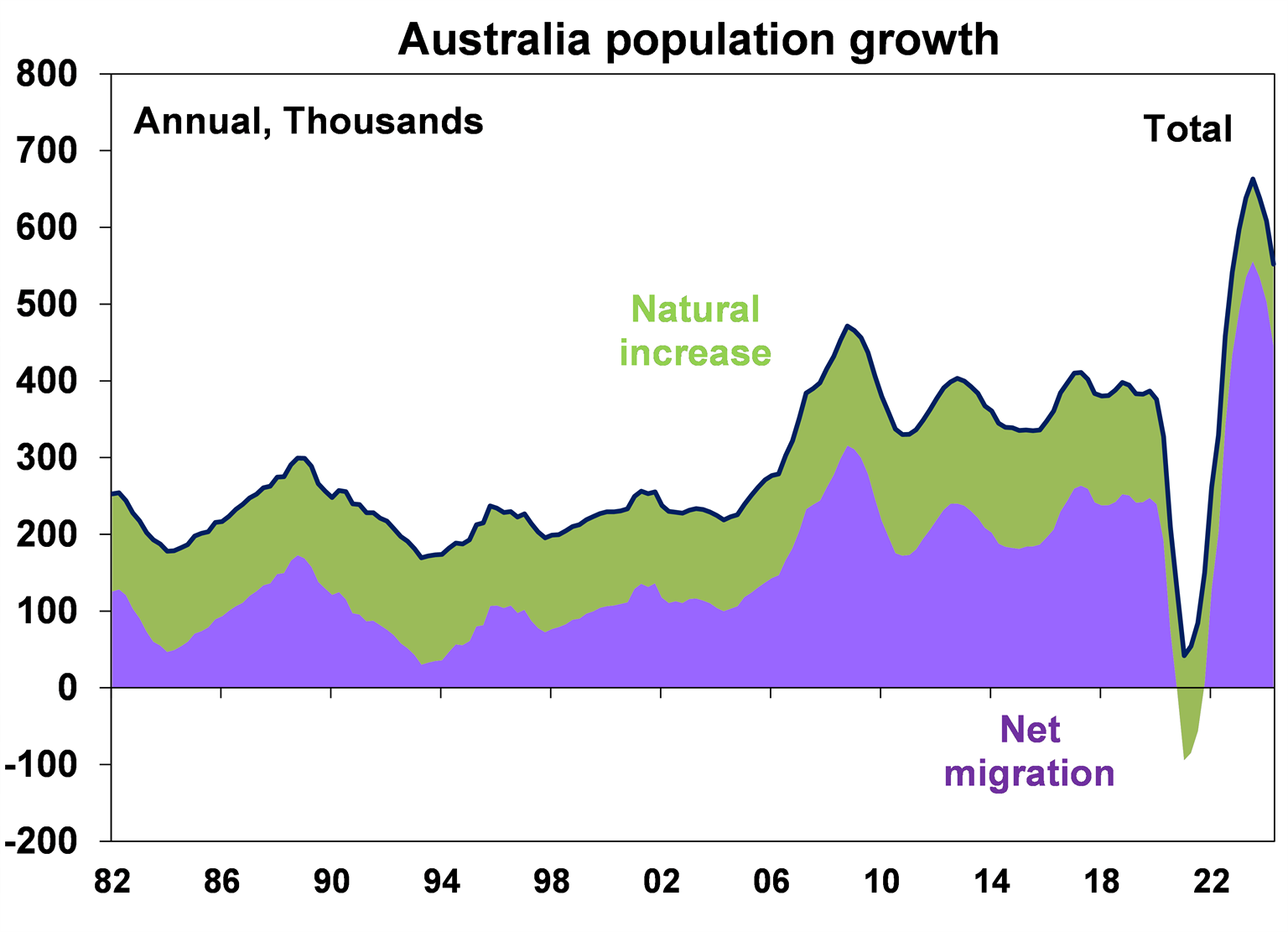

According to surveys by Roy Morgan, immigration is one of the top 10 issues shaping the 2025 Federal Election, with a significant increase in voters’ interest since 2022. This is unsurprising, given the record high net immigration levels in the past 2 years (reaching 536k or 2% of the population in FY 22-23) and its impact on the housing shortage.

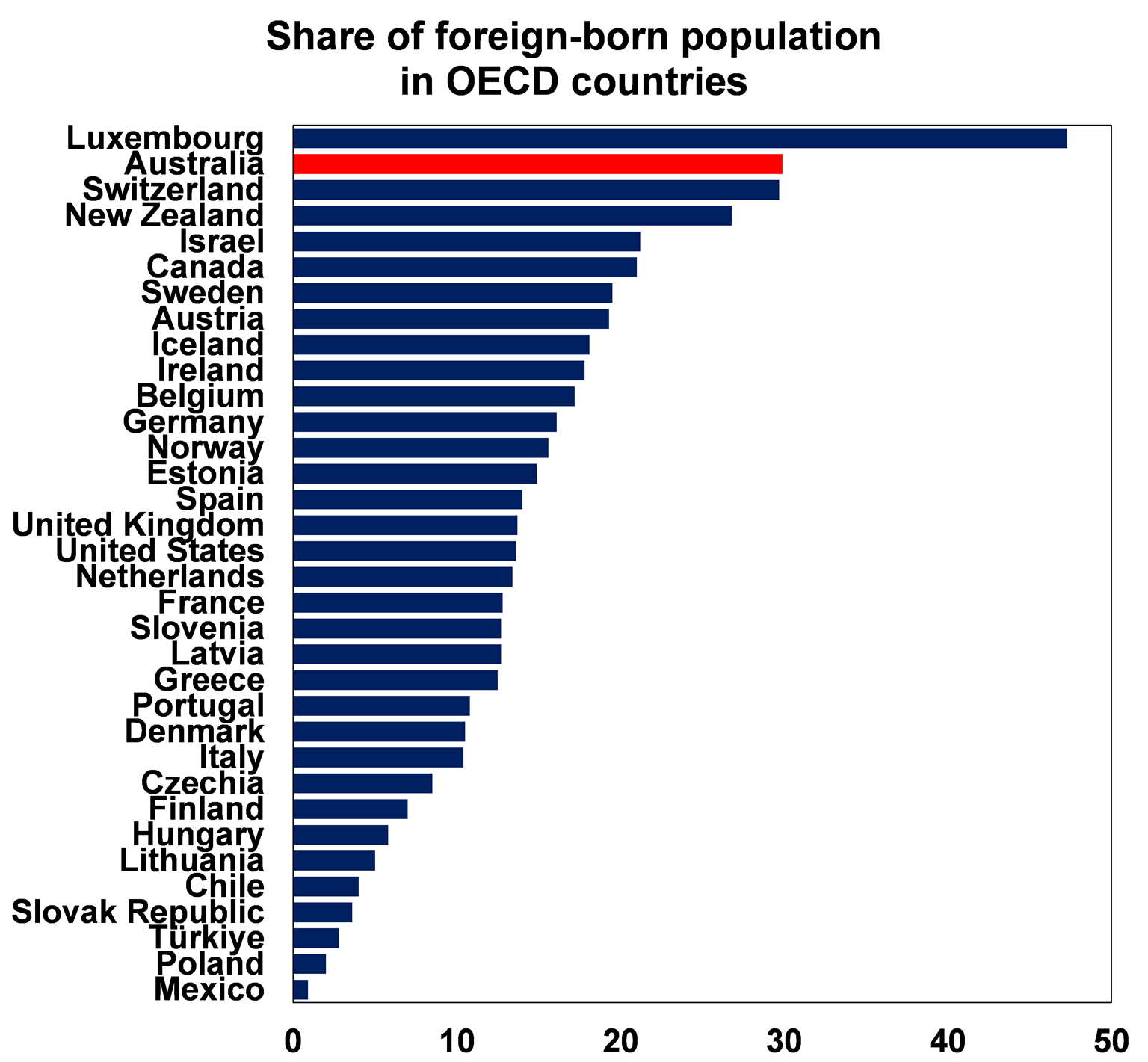

Even before the post-Covid surge, Australia always had one of the highest shares of migrants among peers. According to OECD data from 2019, 30% of the Australian population was born overseas, more than double the OECD average of 14%. This figure was only 23% in the early 2000s. Overall, net migration has outpaced the rate of natural increase since 2006, accounting for more than 60% of population growth in Australia since then.

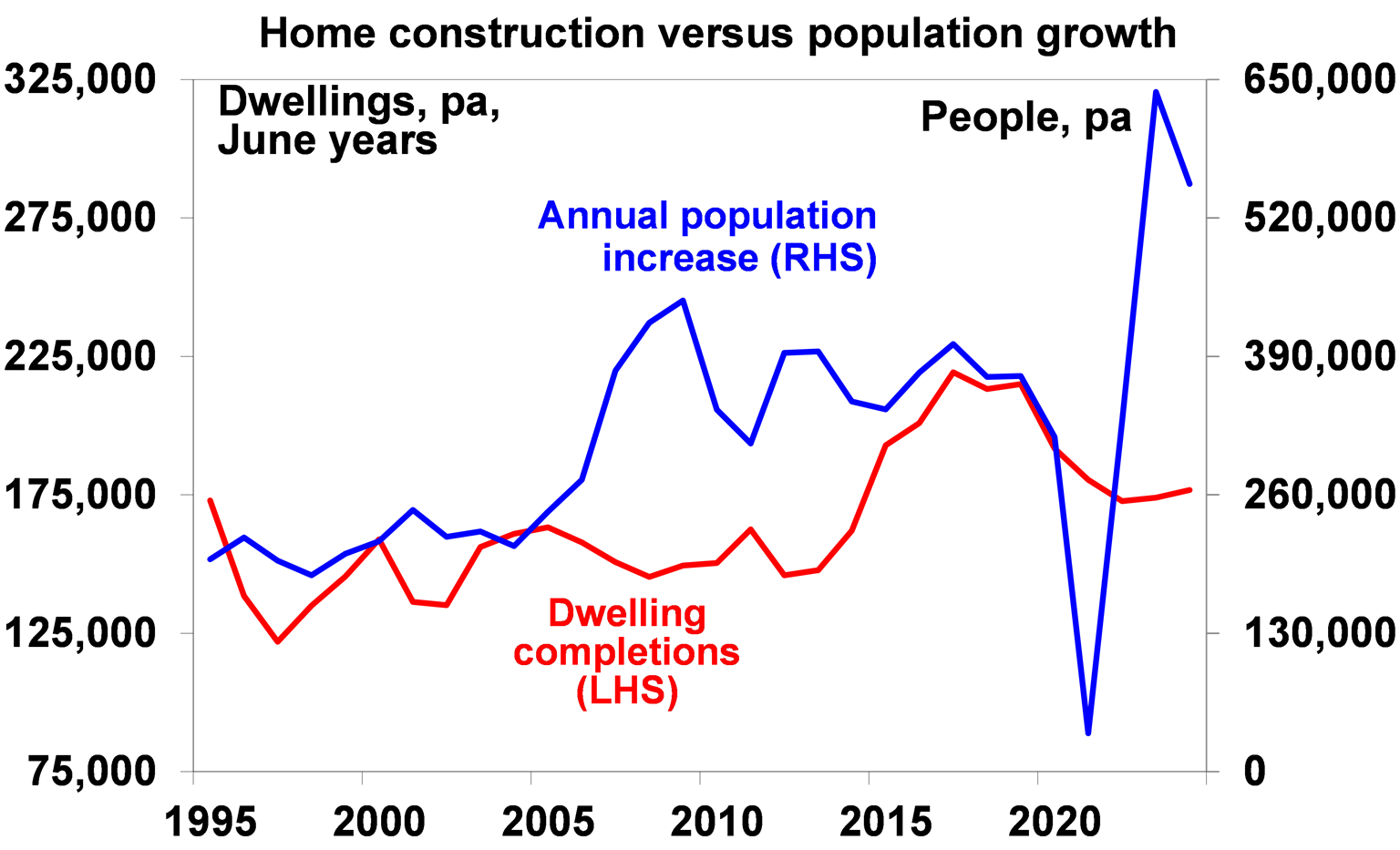

Population growth, either through natural births or immigration, increases both supply and demand in the economy. More people create additional consumer demand and labour needs, boosting GDP (Australia avoided a technical recession in the last two years largely due to population growth, with GDP per capita still 1.6% below its peak in 2022). The flip side is higher demand can also increase inflation, especially in poorly balanced sectors such as housing, where dwelling completions at 176k units in FY23-24 were way below demand for at least 240k residential units.

On the supply side, population growth can also increase the size of the labour force. However, it is contingent upon the characteristics of the additional population. The skillsets of the new entrants are also significant, as well as their ability to integrate into the local labour market.

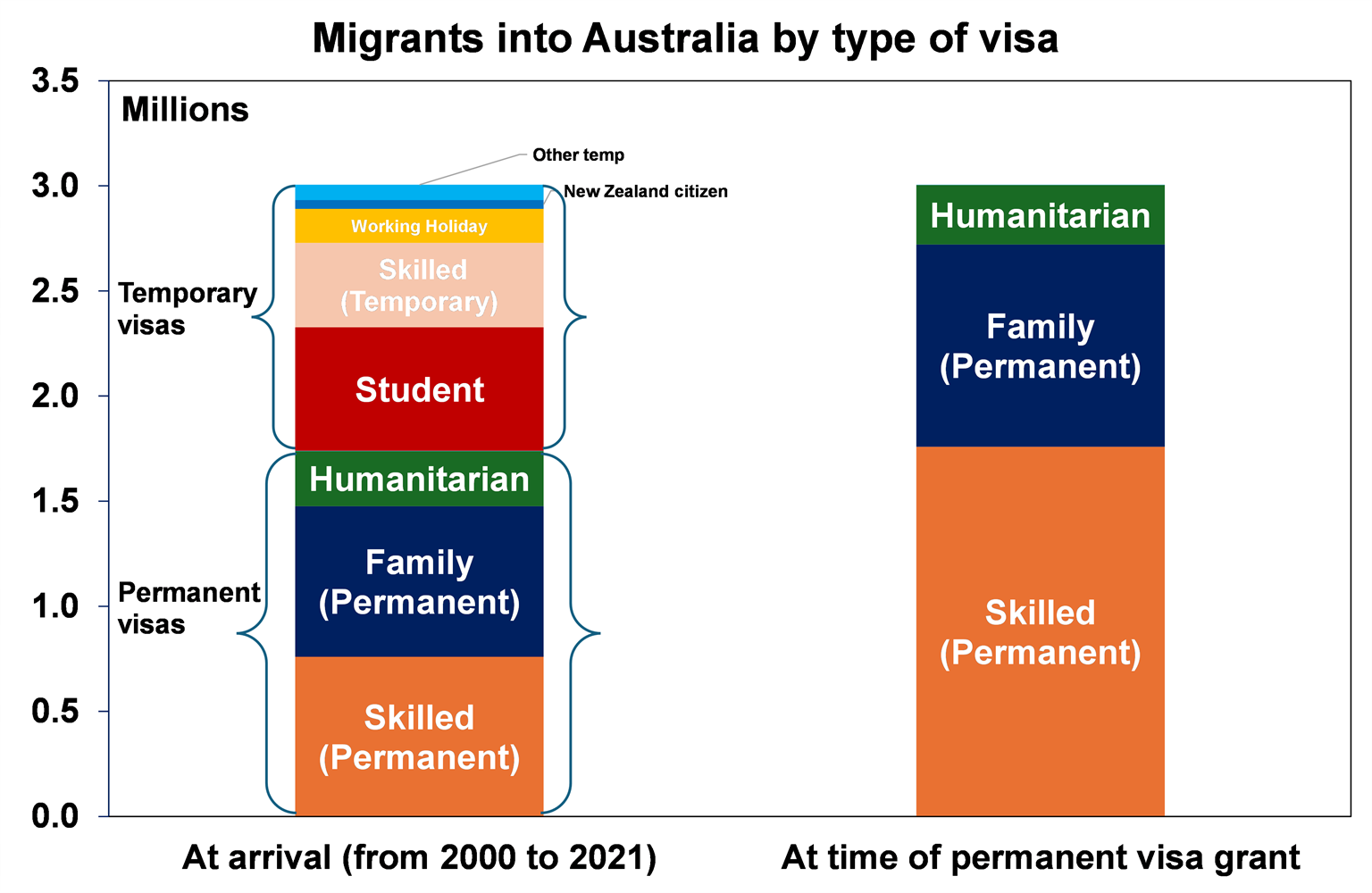

Therefore, the impact of additional immigration on the economy can vary widely depending on the migrant population composition, which has shifted over the past 20 years. Net migration to Australia now increasingly consists of temporary students and working holiday makers. However, many of these temporary arrivals eventually obtained permanent residency and settled in Australia through skilled visa programs.

As a result, immigrants in Australia tend to be younger and more educated than the native population, with a larger proportion holding tertiary qualifications. They are also more concentrated in major cities. This article will examine the impacts of these characteristics on the Australian economy over the last 20 years.

Younger population is a positive for the ageing demographics

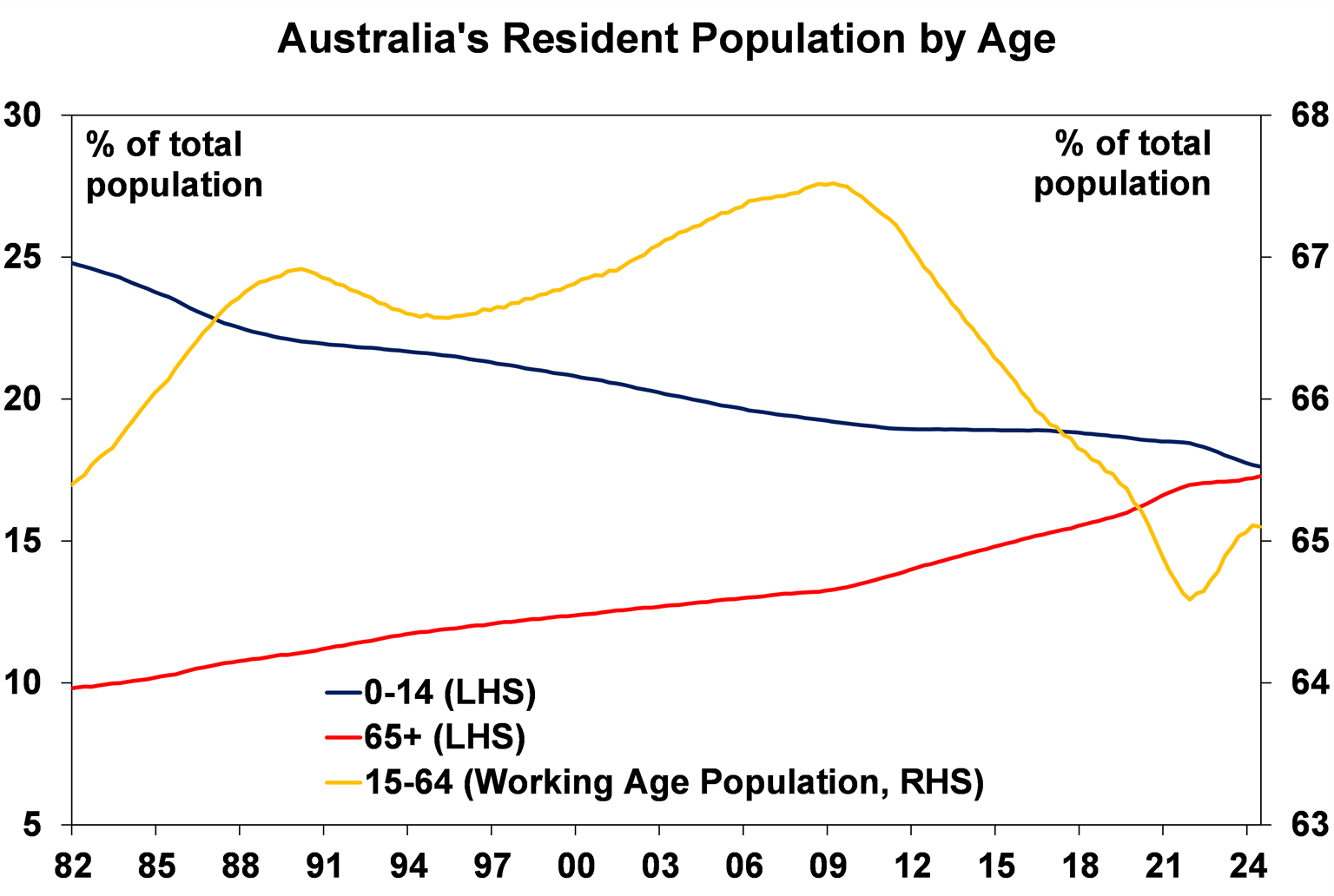

Australia's population is ageing quickly, with births down 17% from their peak resulting in a record low birth rate. Consequently, the median age has risen from 33 in the early 90s to 38.3 in 2021. An ageing population generally increases healthcare and pension costs while reducing tax revenues due to fewer working-age taxpayers. However, in Australia, a strong job market with rising participation and lower unemployment over time has mitigated these effects, along with high immigration levels.

Immigration can mitigate the negatives of an ageing population, as immigrants in the last 20 years are slightly younger on average compared to the overall population (37 years old as of the last census date). In addition, many immigrants have also gained residency through skilled work in healthcare, aged care and social assistance, addressing the demand for retirement care. Notably, 15% of all permanent immigrants from 2000 to 2021 were either Health Professionals or Carers and Aides.

More educated workforce is a positive in the long-term

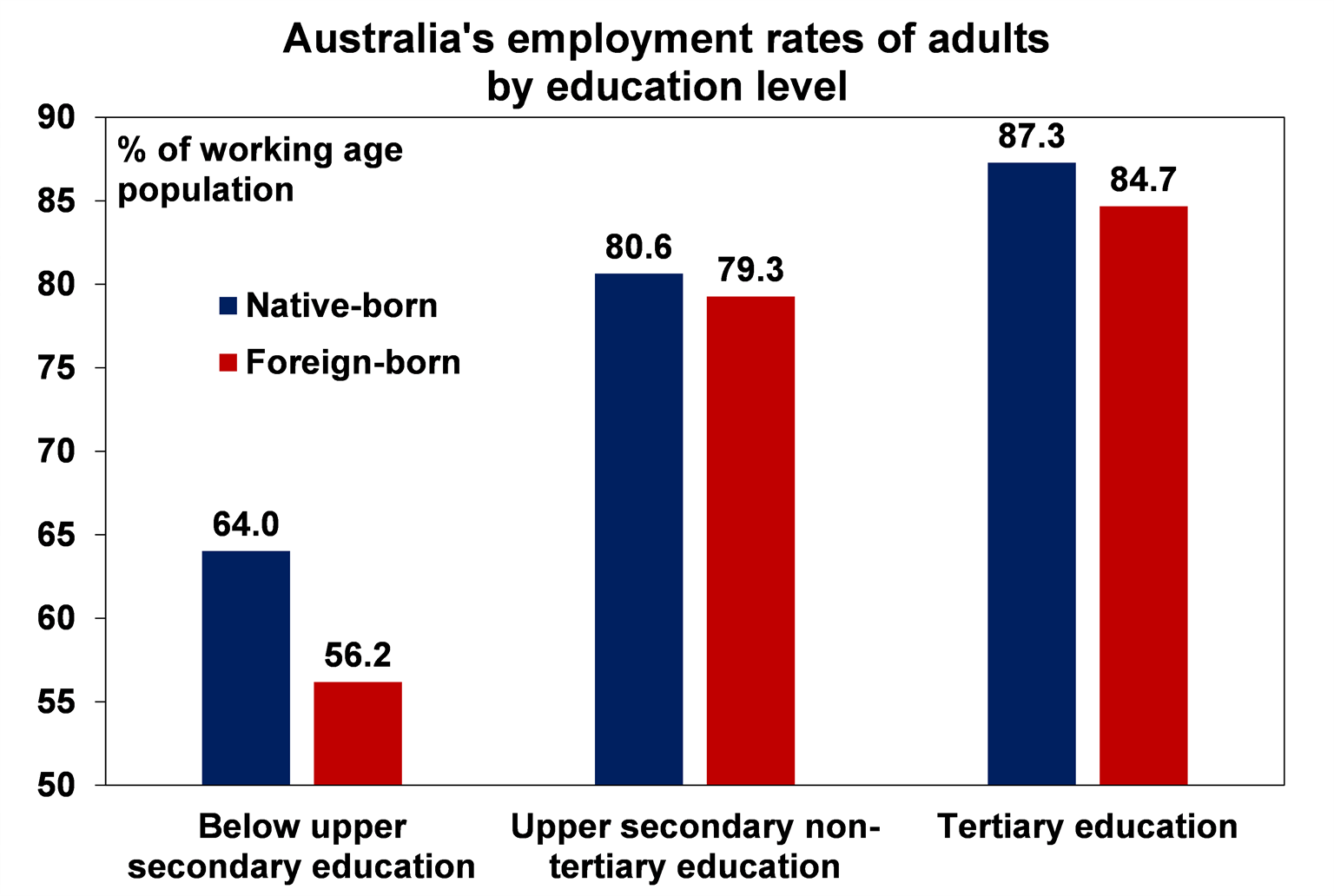

Australia has a highly educated immigrant population. Among individuals aged 15 and above, more than half (51%) of permanent migrants and 39% of temporary residents held a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 29% of the overall Australian population in this age group. As a result, permanent migrants have a slightly lower unemployment rate (4.4%) compared to the overall rate for Australia (4.6%) as of the last census date.

A more educated workforce is likely to be more productive and therefore earns higher wages. In fact, the median weekly income of permanent immigrants in 2021 was $963, compared to just $805 for the overall Australian population. Educated migrants can also complement native workers' existing skills, especially through “skill shortages” visa programs which can address worker shortages.

While these labour market outcomes are a net positive for the overall economy, does it also mean that migrants have crowded out the native-born population for those more lucrative positions? There may be some short-term substitution of the local workforce for higher-skilled migrants, but long-term evidence (which we will discuss below) suggests otherwise, because there is also increased labour demand through a boost to consumer spending from migrants.

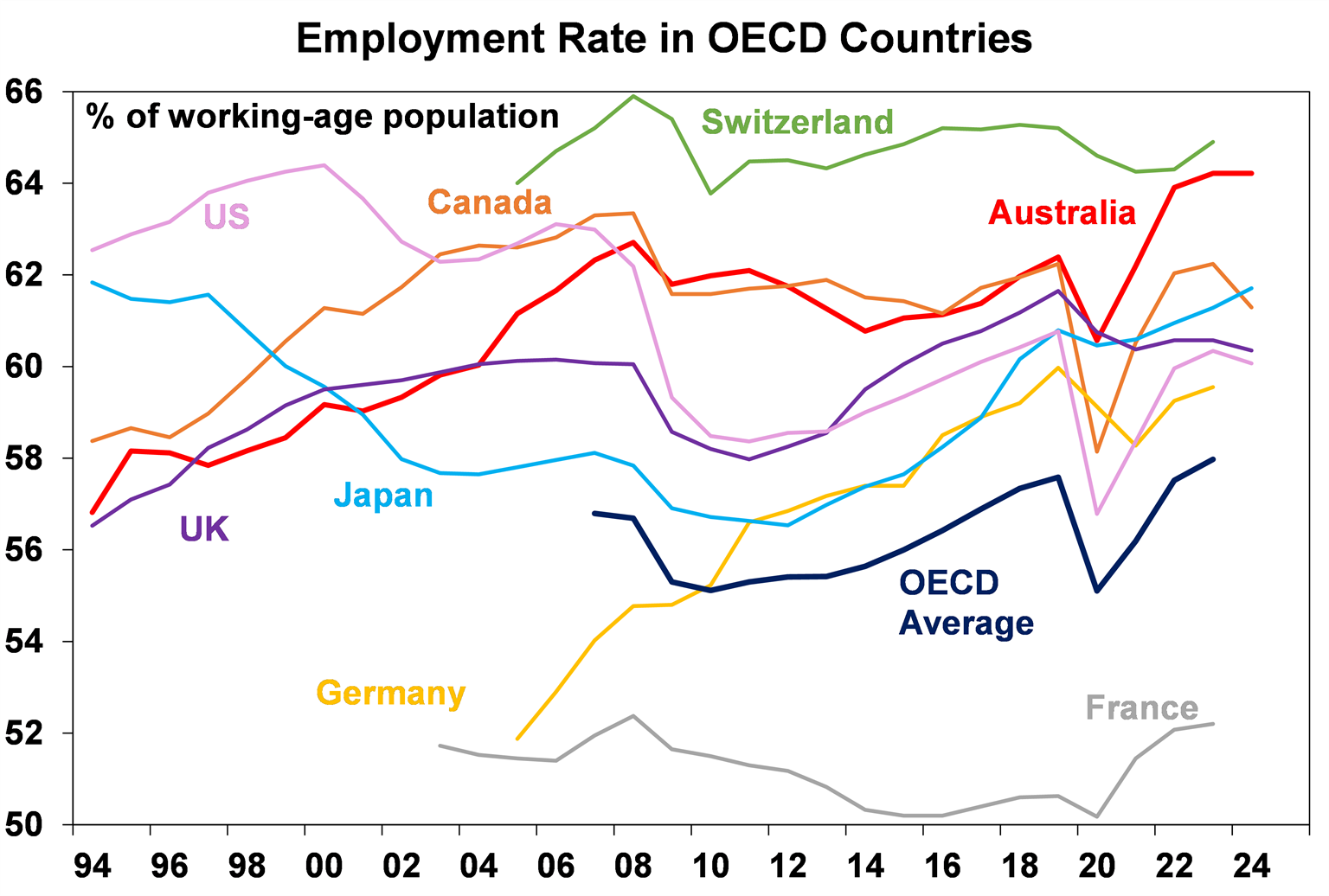

The first piece of evidence is the large uptick in Australia’s employment rate (i.e. the share of the working age population with a job) over the last three decades, from 57% in the early 90s to 64.5% by now. This means that even with many entrants to the labour market, most have been able to be matched with a job. Coincidentally, Australia has seen much better employment rate improvement versus OECD peers, while also having a larger gap between education levels of migrants and the native-born population. This contrasts with countries like the United States, Germany or France, where natives have higher average education levels than migrants.

In addition, after controlling for education level, immigrants in Australia tend to have worse labour market outcomes compared to locals, evidenced by lower participation and employment rates according to a study by the OECD (see chart below). This indicates that highly educated immigrants encounter more challenges in securing jobs that match their qualifications, because degrees might not be transferable or recognised across borders. The probability of being “over-qualified” for certain roles also further discourages labour force participation. In short, the native-born population still has a better chance of landing a job, everything else equal.

Housing shortage is a major negative externality

Unsurprisingly, a younger and more educated population (i.e. recent immigrants) tend to settle in regions with high education levels and low unemployment. That is primarily capital cities, where the housing shortage is more severe. The majority (56%) of recent migrants live in Sydney and Melbourne. Meanwhile, only 13% of immigrants live in regional areas, compared to roughly one-third of native-born Australians.

Consequently, the recent wave of immigrants might not have adequately addressed the skill shortage problems in regional areas. Compounding this issue is the fact that immigrants are less likely to work in construction compared to the Australian-born population (only 2.8% of migrants who arrived within the last five years are employed in construction), thereby exacerbating the construction labour shortage. This has pushed new dwelling inflation to a high of 20.7%yoy in 2022, though this figure has now dropped to just 2.9%.

We have written about immigration and housing affordability previously here. In short, the key drivers of expensive housing in Australia have been a mismatch between new housing demand and supply, except for a brief period between 2017 and 2019. While population growth continued to boost demand, it has not been matched by an increase in supply of housing construction, due to both material and labour shortages (see the chart below).

There is some upside for housing construction going forward as new dwelling cost inflation moderates. However, getting supply back up to match demand is unlikely to be achieved within the next year – given the current approval and construction time (both have risen versus pre-covid levels), combined with still low levels of apartment approvals in the mix (~40% of total dwelling approvals, compared to 50% back in the 2015-17 period).

The outlook

Australia’s natural population increase is projected to decline over the next decade as the total fertility rate remains low, reflecting the trend of women having children later in life and having fewer children overall.

However, with an ageing population that requires significant government support and benefits, positive net migration is probably essential, particularly to boost the healthcare and aged care workforce.

In the short term, house prices will undoubtedly be supported by the ongoing demand and supply imbalance and there is a need to adjust migrant intake to align with existing housing supply capacity.

But in the longer term, there is a clear benefit to attracting highly skilled and more productive workers that complement the local population. However, this requires a less punitive income tax system and a better designed skilled visa pathway for genuine areas of shortage, such as the construction industry. Finally, there is a need to reduce concentration of population in major capital cities, where competition for housing is already intense.

My Bui, Economist, AMP

Important note

While every care has been taken in the preparation of this document, neither National Mutual Funds Management Ltd (ABN 32 006 787 720, AFSL 234652) (NMFM), AMP Limited ABN 49 079 354 519 nor any other member of the AMP Group (AMP) makes any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This document is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.

This document is not intended for distribution or use in any jurisdiction where it would be contrary to applicable laws, regulations or directives and does not constitute a recommendation, offer, solicitation or invitation to invest.